this too... shall pass

on madness, memory, and turning 27

From the ages 22 to 25, I was deeply, terribly schizophrenic.

It started as whispers. I thought I was hearing neighbors mumble through the apartment walls. Then, I realized they were talking about me! — my every action, my every thought. They delivered scathing commentary on my guitar playing, my social skills, and my sexual habits. They mocked my flaws and inadequacies. They called me the ‘great pretender’. And as irrational as it was, I couldn’t help but listen.

Then, the paranoia set in. I knew people were watching me from the apartments across the street — but I couldn’t prove it. I would peek out the blinds at night, trying to catch them in the act. I became convinced that my neighbors were spreading pictures of my dick around the building. In public, I felt eyes following me from miles away.

I called my therapist beside an empty building by the railroad. (My apartment was no longer a safe place to speak.) He expressed his concern but said we still couldn’t meet — we were, after all, in a worldwide pandemic. I suddenly got the sense that someone had their ear pressed against a nearby wall, so I ended the call. We never spoke again.

The voices grew louder.

They developed three distinct personalities — a man and two women. The man was sharp and incisive, and dissected my insecurities with clinical precision. The first woman was shallow, judgmental, and cruel. She liked to see me hurt. The other was naive and curious but trusted the other two implicitly. They became my constant companions, my ‘neighbors’.

I moved out of that apartment and back into my childhood home. The voices followed.

One evening in a cannabis-induced haze, I experienced a full-blown chorus of spiritual condemnation. He doesn’t believe in God! The ‘neighbors’ whispered to one another, hot with disdain. What? He doesn’t believe? He doesn’t believe in God! Tears ran down my cheeks. My mom wandered by and asked what was wrong. But I was frozen. I couldn’t speak, couldn’t make eye contact. I stared off into space. She shrugged and left me alone.

I moved to Baltimore, where I worked in neurology clinics. The voices followed, yet again. Sometimes, after a long day of working with patients, the illusory insults would subside. And for a brief moment, I hoped that I was free, that I had imagined the whole thing. But they always came back. And each time, I sank deeper into despair.

One night, I dreamt I was suspended in mid-air, surrounded by thousands of unblinking eyes, staring from every angle — above, below, all around. Muffled voices spilled over one another. I woke up, yelling: “我听到你!” I can hear you. Then I caught my breath and was embarrassed. I prayed my roommates hadn’t heard.

I could no longer ignore or shut it out. Formless presences muttered from behind every wall, watched me through every window. My thoughts became scattered, incomplete. I could not remember who I used to be. I vacillated between immobilizing anxiety and desperate rage. Every day for months, I fantasized about killing myself.

Still, I refused to consider medication. I was afraid to consult a doctor. What if he confirmed that my mind was broken beyond repair? That my efforts to fight the psychosis were futile? Or, worse, what if he told me nothing was wrong? What if he didn’t believe me?

So I kept the voices a secret. I fought the battle alone. I festered in my shame.

At my lowest point, I reconnected with an old friend — the first close friendship I’d developed since the pandemic started. Whispering haltingly into the phone, I told him my ‘neighbors’ were always listening. I told him they were watching me through the blinds. I told him I was hearing voices.

He could not relate, but he didn’t have to. It was my confession that mattered, the release of a long-kept secret. It heralded the change. It set me toward recovery.

After an endless winter, blew a wind of spring.

So what changed?

First, I started studying for my medical college entrance exam. That gave me the structure, focus, and purpose I’d been missing. From my studies, I learned about the biological and psychological foundations of schizophrenia. I took action: I quit using drugs. I spent more time with friends. I reframed my psychosis as a treatable condition rather than a source of shame.

Most importantly, I started telling people.

I told my mom while parked in my car, tears running down my face, fist slamming the steering wheel. She was aghast but held my hand tightly. I told my sister and my estranged dad. I told my friends one by one, afraid to be abandoned, but knowing if they loved me, they would stay. And they did stay.

And as the real voices of those I loved filled my physical world, the illusory voices in my mind, those formless presences, began to fade.

I moved to New York City, and this time, the voices did not follow. I was still shattered, but in full possession of my mind. I lived only blocks away from Times Square. Most New Yorkers hate this part of town. But I loved it. I loved the tourists, I loved the crowd. I still do. Each time I sink into that sea of people, I’m confronted with my smallness, my insignificance. I remember I am nothing, and my mind goes quiet.

Today, I turn 27.

Even after the voices left, it took me years to rehabilitate, to feel human again. I lost my early twenties to mental illness and my mid-twenties to recovery. But I’m blessed, lucky, grateful that I wasn’t too far gone. Some never make it back. It was my people, their love, and our connections that saved me.

Now, those years of psychosis feel like nothing more than a bad dream. A nightmare dispersed upon waking, the details of which elude. Some days, it’s hard to believe it really happened. The memories are hard to access. Perhaps that’s for the best.

I’m still plagued by anxieties and traumas, deep-rooted relics from my childhood. Often, I cannot control my fear or my anger. Sometimes it still feels like everything is falling apart. But then I consider where I’ve been. And I remember that even the worst of times… shall pass.

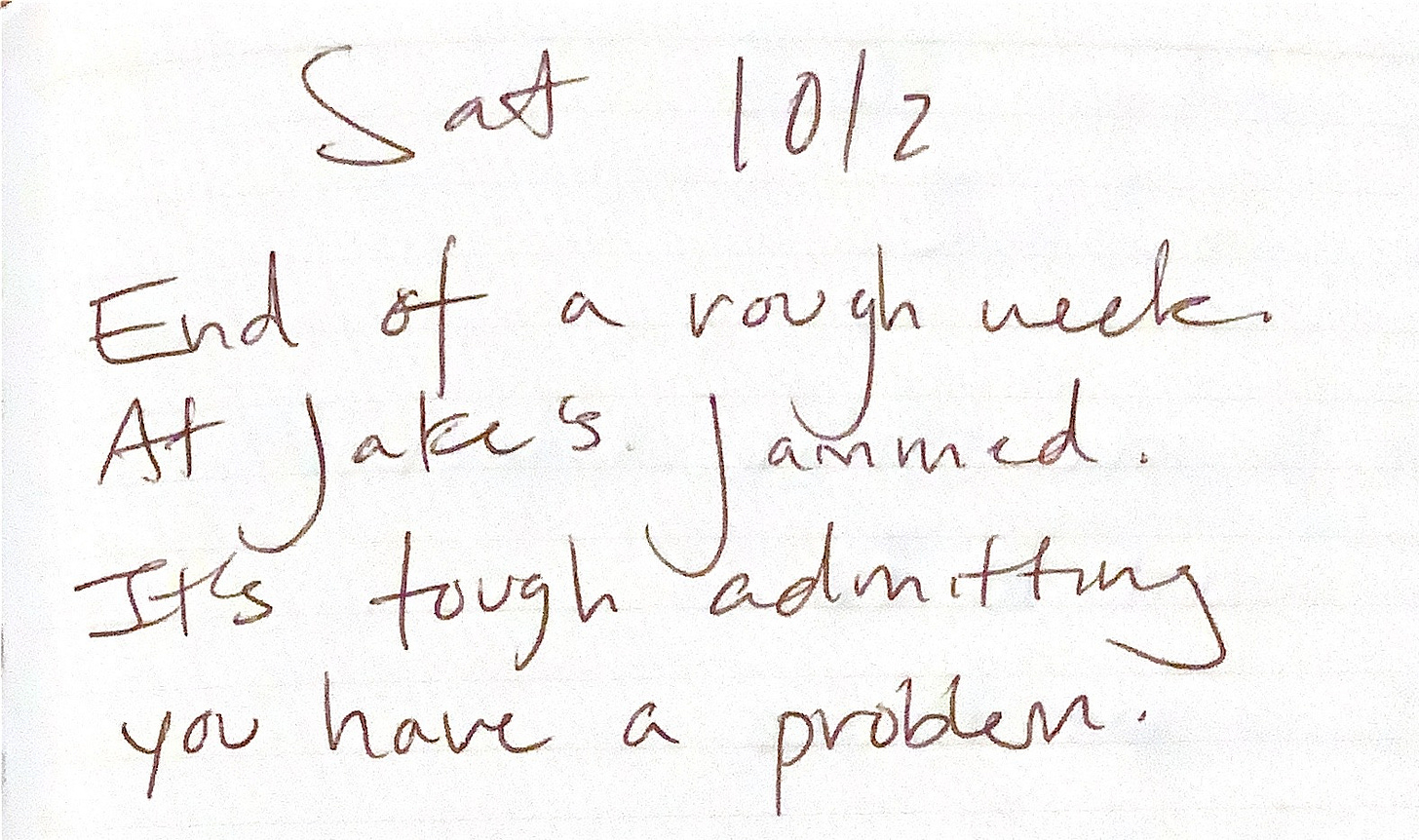

One day, I'll look back on my twenties as a storm I weathered and survived. I'll be surrounded by people I love. I'll have meaningful work that gets me up in the morning. I'll revisit my journals from these troubled times, and I won't identify with them anymore. I will no longer be this scared, lost little boy.

The nightmare will be over.

Beautifully told.

You are very brave. Thank you for sharing.